A CLOCKWORK ORANGE

"What's it going to be, then, eh?"

A CLOCKWORK ORANGE

Fri 21 Oct 2011 to Wed 04 Apr 2012

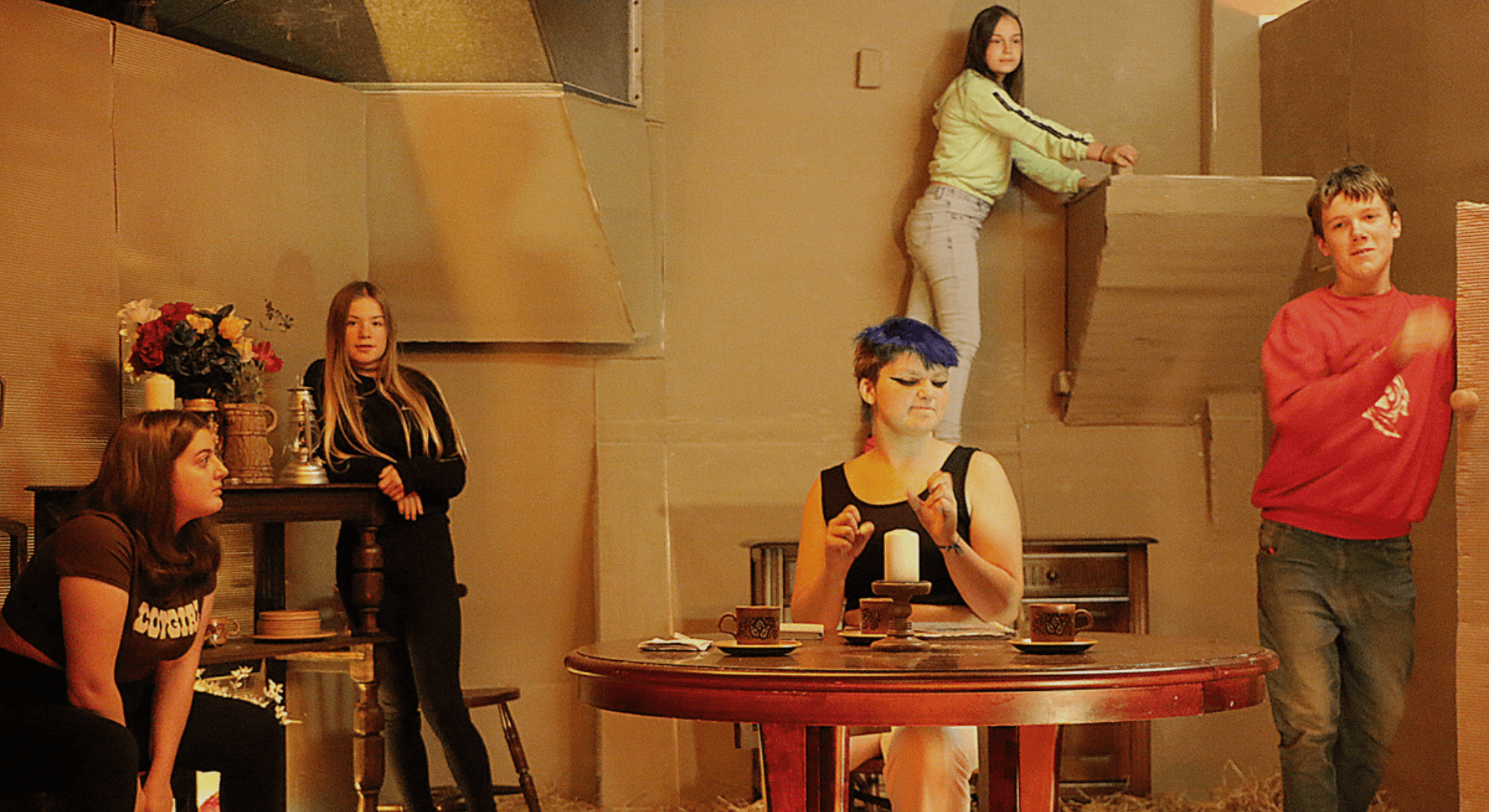

A Clockwork Orange was published fifty years ago, but its portrait of a corrupt state, a bankrupt civil society, and a populace in fear of feral youth seems urgently familiar. In a world like this, how are the nation’s young people to behave? There is, at least, much pleasure to be had in being violent, drunk, drugged and debauched.

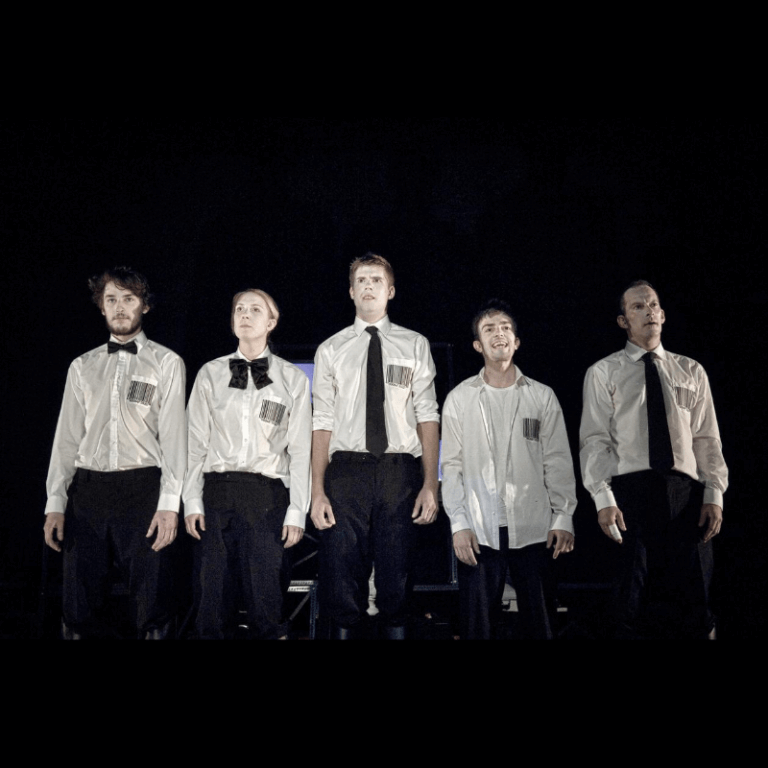

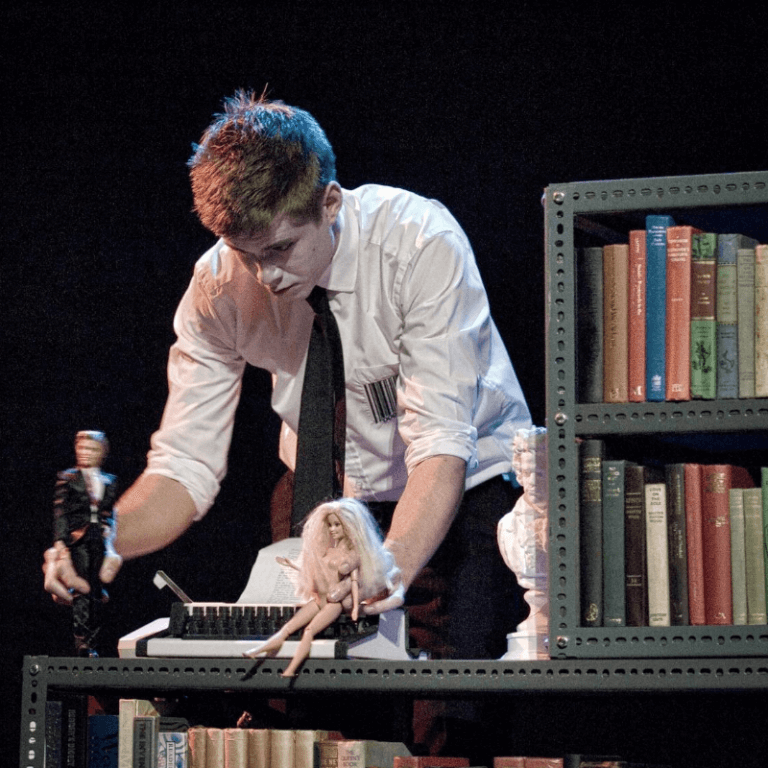

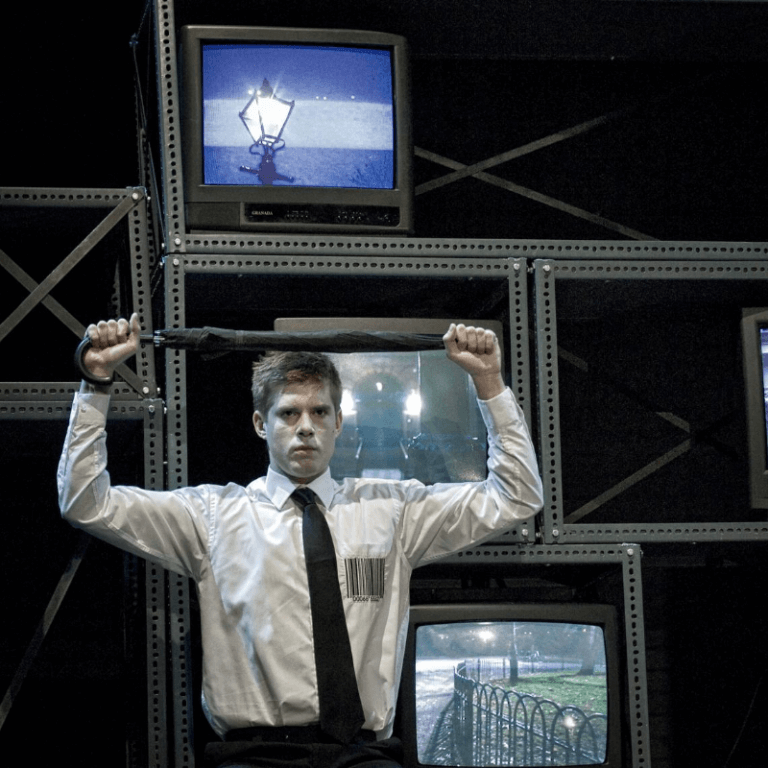

Volcano tackles Burgess’s inventive, disturbing little masterpiece with choreographic skill and linguistic exuberance. A nasty little shocker, or a profound exploration of state power and free will? Beautifully designed, with extraordinary performances, this production stays true to Burgess’s original in its cut-throat inventiveness and in its insistence on the question of whether it is better to be forced to be good, or to be free to do evil.

About Volcano’s Clockwork Orange

A Clockwork Orange is, amongst other things, a novel (and a show) about choice. “What I do,” says Alex, “I do because I like to do”.

You might or might not have read the book. You might or might not have seen Kubrick’s 1971 film adaptation, but you are unlikely to have escaped the reach of its iconography. It’s fair to say that it is the Kubrickian Clockwork Orange that dominates the popular imagination. Volcano’s Clockwork Orange is a different beast. It bears the name of Anthony Burgess not because it reproduces the novel (or subsequent play) in any systematic, mechanical (or even clockwork) sense, but because it share’s Burgess’s sense of unfinished business. Burgess didn’t regard the novel as one of his best, and lamented the fact that it refused to be erased from the world’s memory. But in the wake of bowdlerization, controversy, bans and withdrawals, cult status, and accusations of pornography and immorality, he continued to feel that A Clockwork Orange demanded a response – he held it to account in a kind of reluctant, necessary conversation. This, too, is where Volcano begins.

A Clockwork Orange might be a problem, but we like Burgess’s “little squib of a book” better than he did. We like its inventiveness, its linguistic brilliance, its disturbing relish. We like its pace and its economy, its humour and its seriousness. Matching these qualities on stage is one way in which Volcano’s adaptation seeks to be true to Burgess’s original.

Burgess was particularly concerned that the movie followed the American edition of the novel in dispensing with the final chapter – a redemptive ending in which our charming and horrible young narrator begins to tire of the repetitive violence of his juvenile exploits and look towards the future. He might have been right when he judged that the “moral lesson” of the novel “sticks out like a sore thumb”, compromising the artistic ambition of the book, but Burgess felt that there was little point in writing a novel that merely depicted an unremitting cycle of recreational and state violence without acknowledging the possibilities for change and complexity, and Volcano shares his enthusiasm for transformation. It is in this spirit that we tackle Burgess’s prescient little novel, fifty years after it was written – looking for ways to make sense of it in the present, after everything that it has been through.

For all its innovation and brilliance, Burgess’s novel is an affirmation of a moral principle that is both simple in its rightness and yet troubling in its consequences – that it is better to be a real “living organism, oozing with juice and sweetness” and yet capable of evil, than to be a mechanism without choice, capable only of good.

Volcano’s Clockwork Orange attempts to capture something of that “organism lovely with colour and juice” – the human being endowed with free will, and capable of change, that Burgess celebrated.

“Eat this sweetish segment or spit it out. You are free.”